IN CONVERSATION WITH:

ZEYUAN REN

ZEYUAN REN

(02.07.24)

Adrian Jing Song: Hi Zeyuan, thank you so much for your time. I understand you’re living and working in Shanghai at the moment. What has it been like navigating the contemporary art scene over there?

AS: I’m wondering if you could elaborate further on the path being “less clear”?

AS: You recently graduated with an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Could you tell us more about your experience pursuing your practice-led research abroad?

AS: Were there any specific suggestions from your instructors that significantly impacted your development?

AS: You mentioned relying on writing as a means of marking progress and re-adjusting your coordinates. Did this interplay between writing and visual practice help shape the conceptual direction of your work?

AS: In Coast to Coast (preamble), the film oscillates between personal encounters, remnants of the past, and several proxies. Could you tell us more about the personal journey that inspired this project, and what compelled you to embark on this exploration of identity and belonging?

AS: Looking ahead, you’ve mentioned that Coast to Coast will be divided into several chapters addressing subjects such as oceanic epistemology, the imagery of the vessel, and the historical legacy of optical navigational devices along the Chinese coast. How do you plan on navigating such an ambitious project?

AS: You were born in Ningbo, a coastal city in the Zhejiang province. I’d love to know more about your upbringing and how you came to pursue a fine art practice. Also, whether growing up by the water influenced your fascination with the coast?

AS: This period of self-discovery sounds incredibly inspiring, could you share the books and exhibitions that sparked your exploration?

AS: Great books! Thank you for such a fascinating conversation Zeyuan. What is inspiring you at the moment, and what do you have planned for the future?

︎

REN Zeyuan (b. 1997) is an artist currently living and working between Shanghai and Ningbo. He holds an MFA in Photography from Rhode Island School of Design and cross-registered at Brown University. Spanning lens-based media, installation and performance, his practice is rooted in the composite experiences of displacement between coasts, ruminating on liminality in the context of historical and geographic specificity. His works have been exhibited and screened at venues including Alchemy Film and Moving Image Festival (2024), de Young Museum (2023) and Microscope Gallery (2023). He was the finalist of the UCCA Lab Emerging Artist Program in 2022.

To see more work by REN Zeyuan, visit Website / Instagram

︎

Zeyuan Ren: Hi Adrian, thanks for having me. It's an honor to be talking to you about my recent art practice. Yes, I actually just moved to Shanghai, and to be more precise, I've been travelling between Shanghai and Ningbo. Compared to an early-career artist in the U.S., the path and situation for an emerging artist in China seems to be less clear and guaranteed but still full of possibilities.

AS: I’m wondering if you could elaborate further on the path being “less clear”?

ZR: The domestic contemporary art scene feels chaotic. Some prestigious institutions tacitly accept the vacancy of an artist’s fee, and refuse to cover production costs or even shipping expenses. In addition, there are still few foundations and mid-sized institutions supporting emerging artists. However, I have noticed some positives, such as the growing emergence of alternative spaces and small galleries which accommodate younger and diverse voices to a certain extent.

AS: You recently graduated with an MFA from the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). Could you tell us more about your experience pursuing your practice-led research abroad?

ZR: I was talking to my cohort about our graduation last year, and we felt like it happened a century ago — time flies, and objective time seems to be compressed. My experience at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) has had a foundational and profound impact on my self-awareness and artistic practice. I feel incredibly fortunate to have spent two fulfilling and productive years with my peers and instructors in such a diverse and tightly-knit department. They have been extremely caring and supportive throughout, and I'd like to express my gratitude for their forward-thinking suggestions and guidance in both seminar and critique modules.

Being suddenly displaced into an academic environment with a different language and culture was stressful, especially within the intense pace of producing new stuff every three weeks. The first year was challenging for me, it led me to keep self-questioning, but also made me trust my intuition and bodily instincts even more (where to go, stop, and start). The process of convincing myself has been lengthy and torturous. Since it was a struggle for me to convey my thoughts during the studio visits and critiques at the beginning, I turned to writing, writing letters to myself — as a way of marking the progress of work and even re-adjusting my coordinates accordingly. I also find myself relying on the latency of time and the making of distance in both my writing and visual practice, whether actively or passively. The nature of the former one resembles latent images on film negatives, waiting to be developed. The latter one manifests in the fact that what I was contemplating here and now was the history and time of another place.

AS: Were there any specific suggestions from your instructors that significantly impacted your development?

ZR: In practice, I was once told by my instructor that my desire to make each experiment perfect led to restrictive choices when facing risks. A well-controlled and programmatic approach actually erased many possibilities. Also, think less and do more.

AS: You mentioned relying on writing as a means of marking progress and re-adjusting your coordinates. Did this interplay between writing and visual practice help shape the conceptual direction of your work?

ZR: The interaction between the writing and visual practice sometimes provides temporary answers to some confusion, but more often it leads to further unknowns (possibilities). If I were to pinpoint a beginning, I believe the conceptual direction of the work is based and shaped more by my visual experience, that is, intuition precedes any sort of written production. When writing, primarily about my practice and visual material, I try to displace myself (as a visual practitioner) as much as possible. It's tough for me to describe this in words, but I do think it maximizes the effect of “interplay" or reciprocity between the two.

AS: In Coast to Coast (preamble), the film oscillates between personal encounters, remnants of the past, and several proxies. Could you tell us more about the personal journey that inspired this project, and what compelled you to embark on this exploration of identity and belonging?

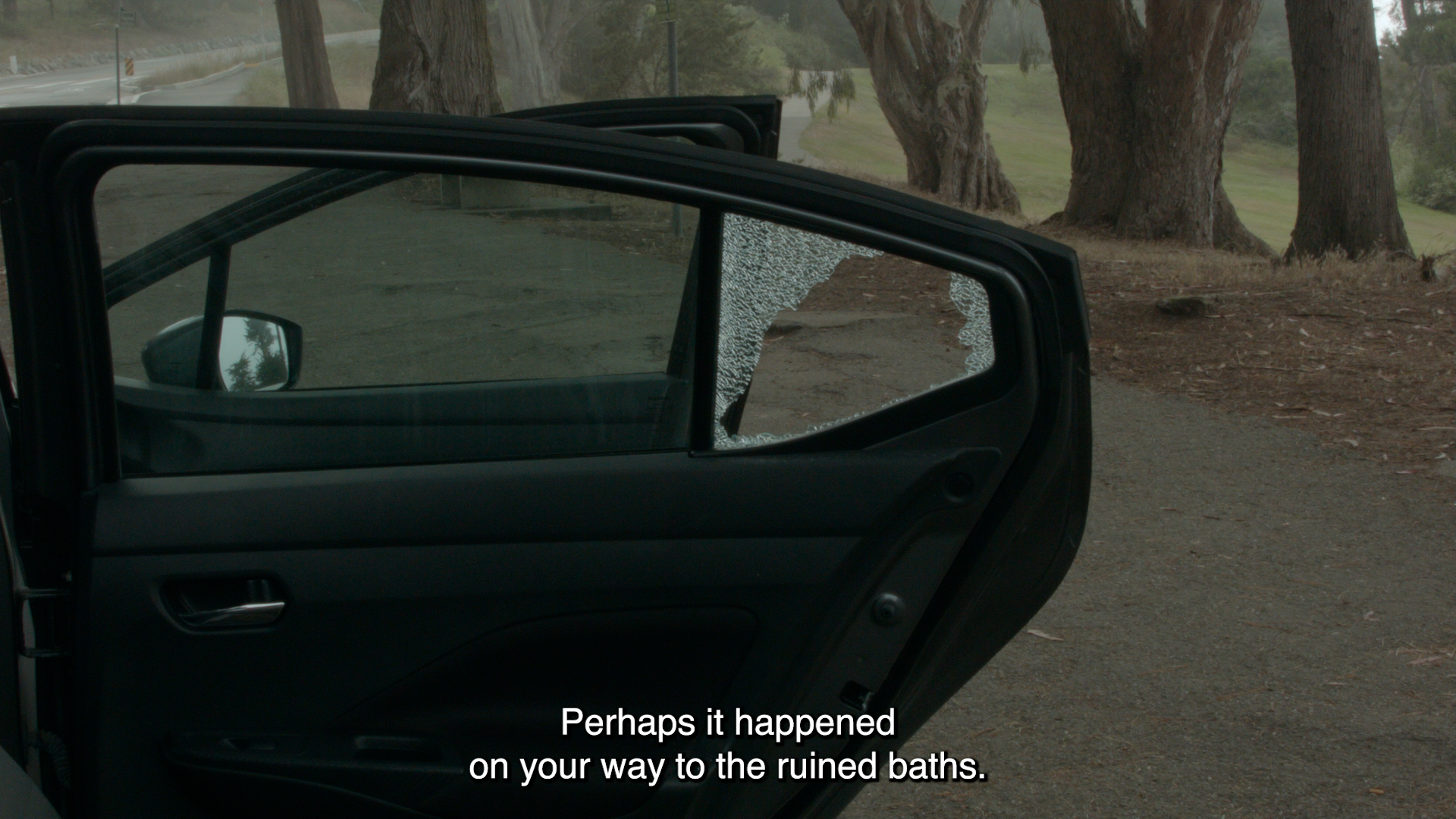

ZR: In the summer of 2022, due to China's ongoing strict quarantine policies, I decided after much deliberation to forgo returning home. This was my first summer spent abroad. Living and creating on the East Coast of the United States, I felt a strong sense of "non-belonging," so I planned to head to the nearest point to my homeland, the Pacific Coast. I chose San Francisco also because I had always longed to visit the Sutro Baths by Lands End. This abandoned bathhouse, shrouded by year-round salt spray, evokes a sort of romance and nostalgia. It also serves as a reminder of the deaths and accidents from the past, the precariousness, and the inhuman forces of the Pacific.

A two-week journey along the coast offers the possibility of seeking a sense of belonging for myself, and the unexpected incidents of those encounters also drew me into the narrative on the coast. For example, I was only going to shoot some empty shots at the abandoned baths but ended up saving a homeless person who was bleeding. It was an unusually cold summer day in San Francisco, but he only had a thin short sleeve. The rescue vehicle carefully made its way down the dirt road from the hilltop to the center of the ruins — at that moment, I wasn't sure if I had triggered this incident. Regarding the remnants of the past, I noticed some actions and symbols in addition to specific objects during the trip, all of which were prefixed with re-. For example, as I came up to a small column monument known as the Portals of the Past (it doesn’t appear in the film), I started to reminisce its story — about the remembrance of an earthquake, the remnants of a mansion, the reconstruction following a disaster, the accidental collapse of another, the replacement of a pillar, and the series of restorations and retrofits.

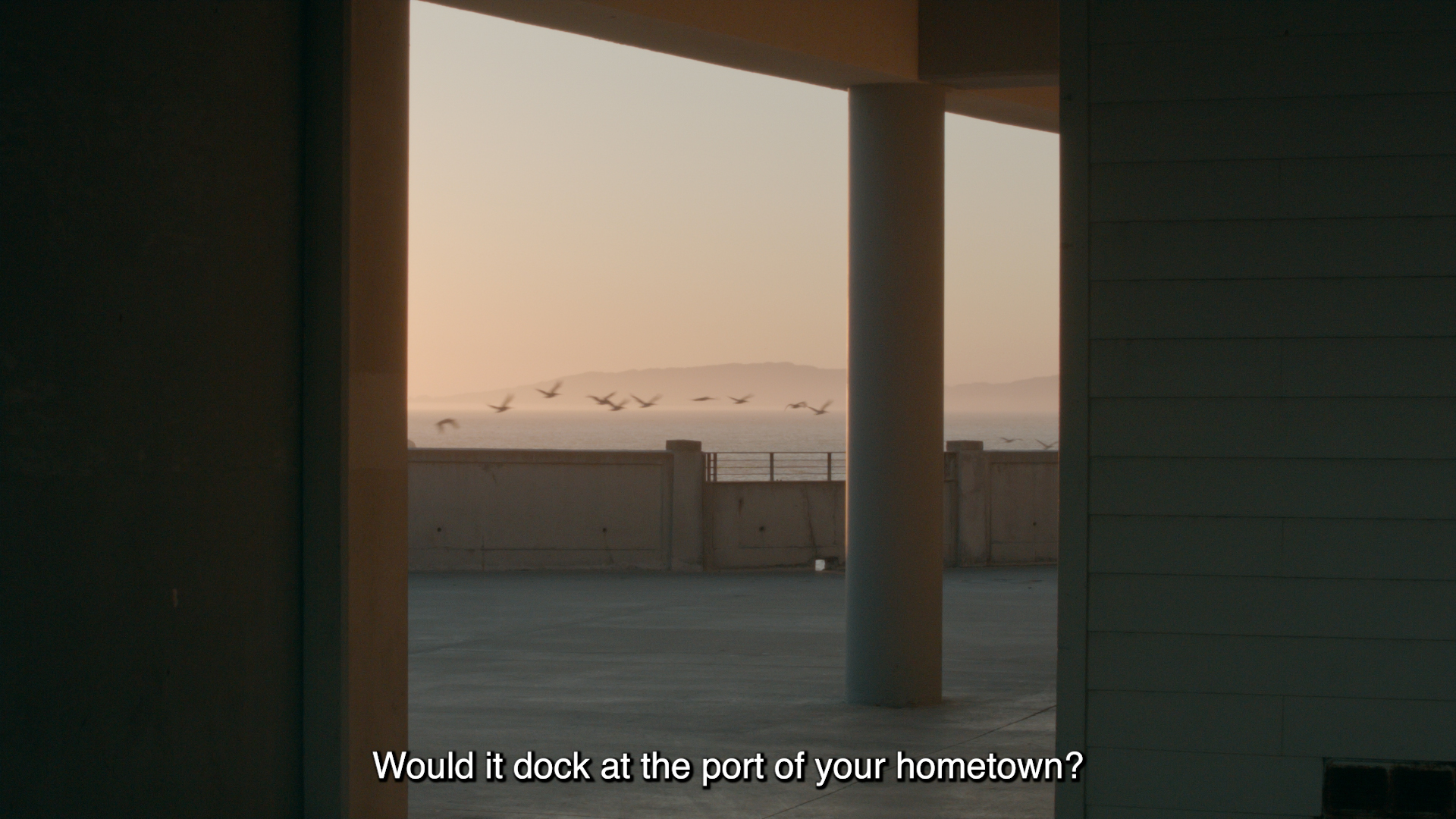

Every time I stood by the coast, I could always see different vessels passing before my eyes, speedboats, cruise ships, and yachts. The ending of the film shows a cargo ship sailing slowly across the twilight Pacific. As I cannot achieve intercontinental travel and cross the Ocean at that moment, in my imagination, it acts as a proxy for homecoming, which will dock in the port of my hometown.

AS: Looking ahead, you’ve mentioned that Coast to Coast will be divided into several chapters addressing subjects such as oceanic epistemology, the imagery of the vessel, and the historical legacy of optical navigational devices along the Chinese coast. How do you plan on navigating such an ambitious project?

ZR: In fact, these subjects can be traced in Coast to Coast (preamble), where they are mentioned but not fully developed. Rather than being "planned" or "drafted," these specific issues are unavoidable in my personal experience and fieldwork. Under these themes lie unarchived objects and potential narratives, waiting to be uncovered and retrieved.

Regarding the theme of oceanic epistemology, the surfers navigate the complex waves, with their surfboards as the extensions of their bodies. Ostensibly, they are maneuvering the narrow foam boards beneath their feet, but they are attuning with the waves. They lead me to reimagine different “ocean users” — such as my ancestors — in the same Pacific. As initiators and participants of one of the earliest seafaring activities in China, did they treat their canoes and wooden paddles as extensions of their senses, embracing the poetics of experience?

This long-term project is research-based. Other chapters address the specific representations of (in)formal imperialism, colonialism, and optical technology in the waters of the Yangtze Estuary in the nineteenth century. Therefore, in my preliminary research, I was required to collect as much archival material as possible, such as cartographic images, proposed drawings, and statistical sheets, to pave the way for the following productions.

AS: You were born in Ningbo, a coastal city in the Zhejiang province. I’d love to know more about your upbringing and how you came to pursue a fine art practice. Also, whether growing up by the water influenced your fascination with the coast?

ZR: My upbringing initially mirrored that of many, with my parents hoping for me to excel in a particular skill. Thus, I began learning Chinese calligraphy from a very young age, persisting until high school, almost 13 years. However, the practice of traditional calligraphy is demanding for a child — grappling with obscure ancient texts and maintaining long-term focus, compounded by my father's impatience for immediate results, gradually led me to rebel against this traditional art form during my rebellious phase. I gradually developed a preference for being outdoors rather than indoors, moving rather than sitting still, which is the reason I didn't choose painting. I got my first camera in high school and began taking photographs, continuing into undergraduate study where I pursued a photo major. During this period, my understanding of photography as a medium was limited to direct documentation and representation. After my sophomore year, exposure to various photobooks and artist books, along with exhibitions and publishing projects centered around locality and historical narratives, sparked an interest in interdisciplinary practices of diverse artists with their field experience, providing me fresh insights into lens-based media, including image-making, prompting me to embark on new creative ventures. Reflecting on my journey, calligraphy is essentially a time-based art that has laid the groundwork for my current practice.

I see the fascination here not in a romantic sense, but rather as an interest in liminal and overlapping spaces such as coast(scape). Unlike traditional borders that enforce strict delineations, the qualities of the threshold formed by coast/shoreline are indeterminate and in flux. These qualities prompt me to reconsider notions of (non-)normality, particularly in the context of our turbulent times and contemporary life. Furthermore, my concern with the ocean transcends literary or metaphorical levels; instead, I contemplate models of time and historical processes while standing at the lands’ end. I'm curious whether the tides or the ocean itself can serve as a paradigm for re-examining these issues. These reflections stem from my composite experience of being displaced between different coasts in recent years — arriving, departing, sojourning, and wayfinding from Ningbo to Providence to San Francisco.

AS: This period of self-discovery sounds incredibly inspiring, could you share the books and exhibitions that sparked your exploration?

ZR: I’m deeply impressed by two exhibitions from 2017 that have significantly influenced my initial practice. One was The Port and the Image I: Documenting China's Harbor Cities at the China Port Museum in Ningbo, and the other was the Frontier – Re-assessment of Post-Globalizational Politics at OCAT Shanghai. As for publications and projects I favor, I would include the artist book by Cheng Xinhao, published by Jiazazhi, centering around his hometown in Yunnan Province, as well as Sam Contis’s Deep Springs and Fumi Ishino's Rowing a Tetrapod, both published by MACK. Although they were released a few years ago, I still revisit them often.

AS: Great books! Thank you for such a fascinating conversation Zeyuan. What is inspiring you at the moment, and what do you have planned for the future?

ZR: Thanks for the questions you prepared. Though the time for myself is currently fragmented, I'm still reading and researching for the new project. Besides that, I visit temples during nice days, listen to sutra chanting, and have conversations with my grandma. The only plan for the future is to have more time to make more new stuff.

︎

REN Zeyuan (b. 1997) is an artist currently living and working between Shanghai and Ningbo. He holds an MFA in Photography from Rhode Island School of Design and cross-registered at Brown University. Spanning lens-based media, installation and performance, his practice is rooted in the composite experiences of displacement between coasts, ruminating on liminality in the context of historical and geographic specificity. His works have been exhibited and screened at venues including Alchemy Film and Moving Image Festival (2024), de Young Museum (2023) and Microscope Gallery (2023). He was the finalist of the UCCA Lab Emerging Artist Program in 2022.

To see more work by REN Zeyuan, visit Website / Instagram

︎