IN CONVERSATION WITH:

TEVA COSIC

TEVA COSIC

(06.11.21)

In Conversation with Sophie Spence

Sophie Spence: Your work talks a lot about nostalgia and personal histories, what is your relationship to nostalgia?

SS: It’s interesting that when you’re going through that process of making images that things come out of it. I get really caught up in the image making process and having a really strong idea from the start, so it’s interesting when these things come out retrospectively as well.

SS: So it’s developed the longer that you look at it in some ways?

SS: These rolls of film, going through a process where things may or may not keep information, draws parallels to how you would actually keep memories. While things are a bit different with phones now, to think that the visual memories we remember have lasted the test of time and make it to your life in this moment is very interesting.

SS: When you’re making a project it sometimes takes a long time to land on. As you were saying, it’s sometimes a process of repair or coming to a point of dealing with things in your own head sometimes.

SS: This really reminds me of the part of your project statement where you say, ‘I invite you to recall your own longings and create dialogues between worlds’, that really struck me. It’s so clever because these items, these moments and these vingettes are special to you and connected to memories that I would never understand, but you invite us into that dialogue around memory.

SS: I also wanted to talk about the construction of the images themselves, who are the people in your images? And what’s your relationship to them?

SS: There was a performative aspect to it as well, were you curating the shots quite specifically? One of your images depicts your mother with a young child.

SS: You also do a lot of self portraiture across both your series. I wanted to ask what the significance of self portraiture is to you and having yourself in these images.

SS: The control you have as well is sometimes really valuable, I think there’s pros and cons to both. Letting things play out but also having control when you’re doing self portraiture. Particularly when shooting film. (laughs)

SS: It’s good to be able to do both. Particularly in lockdown, you’ve got options.

SS: How do you feel about the series, and how do you feel about home now reflecting on the series?

︎

Teva Cosic is an artist based between Naarm/Melbourne and Gimuy/Cairns.

Her research and practice often explore the complex tensions of family and cultural history as they intersect with broader notions of identity, migration and belonging.

To see more work by Teva Cosic, visit - Website / Instagram

︎

Teva Cosic: It’s funny, I kind of arrived at that later. It wasn’t actually the driving descriptive word for the work. I came to it as I was writing my honours thesis because it’s all about migration and nostalgia. It’s only in hindsight that I see the work as nostalgic.

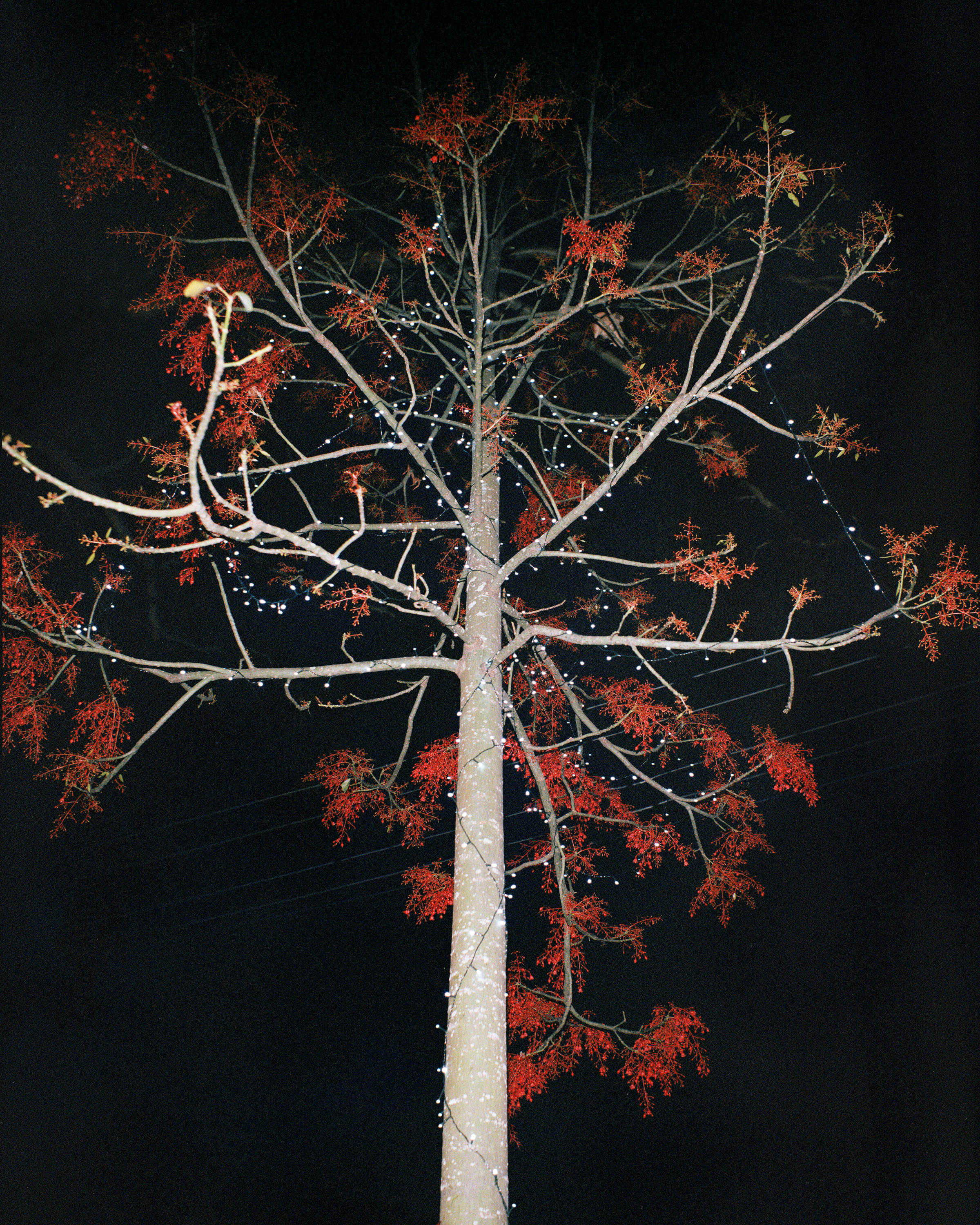

In terms of my process, it was about revisiting places that I went to as a child and thinking about how these spaces are effective and how they carry memories and change over time. When I was younger they meant something different and now coming back, they are very nostalgic. I don’t think it’s anything that was consciously driving my work as I was making it, I didn’t actually land on that word. I was more concerned with thinking about memory, loss and place.

SS: It’s interesting that when you’re going through that process of making images that things come out of it. I get really caught up in the image making process and having a really strong idea from the start, so it’s interesting when these things come out retrospectively as well.

TC: I think it’s nice, and the way I’ve thought about the work has definitely changed [too]. I mean, I made it a whole year ago now and it’s been sitting. It’s evolved in terms of the research I’m doing now, which has come from that project in a way. It’s nice when you look back on work and see things you couldn’t see when you were making it.

In terms of my relationship with nostalgia, it’s kind of hard to describe. I feel like I’m a really nostalgic person, not in a bad way. I don’t know, I get in these moods where it kind of comes over you. I guess that’s what nostalgia is, it kind of affects. It either does something or it doesn’t. It sometimes ignites something and other times it passes by and fades away. When I’m reading the images that I’ve made, I don’t know, I guess I subconsciously created this nostalgic narrative for myself. If that makes sense.

SS: So it’s developed the longer that you look at it in some ways?

TC: Yeah, and the process too was very slow because I was shooting film; in Cairns where I made the work there’s no film labs or anything so I had to wait a long time. I was there for five months last year, I didn’t really want to send that many rolls in the mail either. I think I might have done one lot - maybe 10 rolls. With the rest of them I thought I’ll wait until I get back. But the date kept getting pushed back so I was kind of sitting on these images as well. These rolls [were] kind of latent and I felt like they were these kinds of imminent memories that hadn’t been developed yet. So you’re kind of sitting on this idea of a memory that hasn’t come to the surface. It was interesting in terms of how I made the work because I couldn’t reflect on anything in the process. It was also kind of the idea that these rolls could be lost or damaged. They’re susceptible to all these uncertainties. And maybe in the end they were all black. It was always a possibility that I didn’t make any work. [The work] became a reflection on memory as well; that process of how images change our memories, and they also inform how we remember things. Sometimes I feel like pictures have replaced actual memories.

SS: These rolls of film, going through a process where things may or may not keep information, draws parallels to how you would actually keep memories. While things are a bit different with phones now, to think that the visual memories we remember have lasted the test of time and make it to your life in this moment is very interesting.

TC: I guess it’s kind of like you’re collecting certain things that you want to remember. A lot of the images that I’ve made are premeditated and constructed, as well as traditional documentary style stuff. But in constructing these images I’ve used a lot of past memories from my childhood and how I felt growing up in this place, especially because my parents are from different cultural backgrounds which is informed by upbringing in this small town in Australia. I got frustrated with waiting for images and trying to capture things as they were happening so I feel that the constructed element was helping me process all these thoughts about how I related to this place, and how I related to my memories of growing up in Sweden for a bit when I was younger. I have all these memories from living there which translate, but they don’t to living here. It was always weird coming back to Australia when I was younger because it was quite different. It’s a bit of a transitory space of not feeling quite like you belong or that you’re Australian, but you [also] kind of are. I think making images is a way of processing these thoughts, and trying to translate these weird intangible ideas that float around a lot of the time.

SS: When you’re making a project it sometimes takes a long time to land on. As you were saying, it’s sometimes a process of repair or coming to a point of dealing with things in your own head sometimes.

TC: It’s a weird thing as well, especially when it’s quite personal. Translating these ideas but also connecting to people in the process. I don’t want to make this work just for myself, it’s for other people too. I want it to be seen and I hope that other people can read into it and feel something from it. I feel like other people can relate to having parents from different backgrounds, and the migratory experience of growing up feeling like you’re not Australian. I suppose you could say a lot about that.

SS: This really reminds me of the part of your project statement where you say, ‘I invite you to recall your own longings and create dialogues between worlds’, that really struck me. It’s so clever because these items, these moments and these vingettes are special to you and connected to memories that I would never understand, but you invite us into that dialogue around memory.

TC: When I was writing that I was thinking it’s so subjective, it’s so personal [that] I can never translate to you how these things make me feel. But I feel like there are certain sentiments in images that you can draw out your own nostalgic feelings or memories or things that are universal. Especially with longing and memory. I can’t give you your memories in my images, but I can [try to] provoke them if that makes sense.

SS: I also wanted to talk about the construction of the images themselves, who are the people in your images? And what’s your relationship to them?

TC: A lot of them are just my family; my mum, my sister, my dad, and I also put myself in a lot of the images. I think one of them is a friend from highschool. Mostly it was my family, but I chose them because they were available to me.

SS: There was a performative aspect to it as well, were you curating the shots quite specifically? One of your images depicts your mother with a young child.

TC: I constructed that image from an old archival image that I have of me and my sister. It’s not directly the same. [The original] is a picture of the two of us, and we’re lying down with cucumbers on our eyes. I remember that photograph. I think about it a lot but I don’t remember that moment or the context of what was happening, or what we were doing. It was such a long time ago. My niece is about the same age as I was in that image, and I kind of staged the scene. I asked my mum to lie there, and I got the cucumbers and lipstick and gave it to her and scribbled on her face. It created this weird tension between the past, the present, and the future. And [with my Niece] thinking about my childhood and her childhood, and the uncertainty of her future now with everything that’s going on. It’s this weird overshadowing, it’s very innocent and playful. I was also thinking about how it’s quite sad in a way that we don’t know what the world is going to be like when she grows up. A lot of the time I was constructing things and letting them play out. I wasn’t specifically making them with [the mindset of] I’m going to have this finished product and this is what it’s going to look like. It was more of a stage, setting up a stage and letting things play out. I enjoy the spontaneity of other people’s interactions and I’m not trying to put things in a box or force images to happen.

SS: You also do a lot of self portraiture across both your series. I wanted to ask what the significance of self portraiture is to you and having yourself in these images.

TC: I’ve kind of stumbled upon it as a way of making images, because not all the time you have access to models or people. I’m right here. But it’s [also] a lot more annoying because you have to make sure that the focus is right and setting things up is always harder. It was always about convenience. That particular series I made during the first lockdown down here [in Naarm/ Melbourne]. I didn’t really have anything else and I didn’t want to do still lives… so I guess it’s self portraiture.

SS: The control you have as well is sometimes really valuable, I think there’s pros and cons to both. Letting things play out but also having control when you’re doing self portraiture. Particularly when shooting film. (laughs)

TC: Sometimes [it can be] really frustrating because you want to take a specific image, but it’s so hard if you’re not looking through the viewfinder. Especially if it’s a close up or you want to be centered in the frame. A lot of the time I have props that stand in, then I stand where it was and I move it. I also think self portraiture comes back to the process of it as well. It’s a weird intimate exchange, but you’re the subject and the object and you’re creating this weird relationship between the subject and the object. You are the photographer and the subject at the same time. You’re gazing at yourself in a different way, but I guess I enjoy it. At the same time I like to use other people as well. I’m definitely not just a self portraiture-ist.

SS: It’s good to be able to do both. Particularly in lockdown, you’ve got options.

TC: Yeah, there’s not much else, and it’s good quality bonding time with the self.

SS: How do you feel about the series, and how do you feel about home now reflecting on the series?

TC: It’s a work that I’d been meaning to create for a long time. I wanted to create some kind of record of this feeling of home. I feel like it’ll always be ongoing, it’s not something that’s going to finish or come to a conclusion. It’s fluid and always changing. I don’t feel like it’s something I’ve completed, it’s just something that I’ve done, [and] that I’m glad to have done.

I haven’t really thought about it too much or reflected on it. I feel like it needs more time to sit. I still feel quite close to it, because I’ve also been talking about it with others. It hasn’t slipped off my mind, and the work that I'm making comes from it. It’s something that needs a couple of years, and then I’ll come back to it and see how it’s changed, how I feel about it. Maybe how I’ve evolved or expanded in terms of my making.

︎

Teva Cosic is an artist based between Naarm/Melbourne and Gimuy/Cairns.

Her research and practice often explore the complex tensions of family and cultural history as they intersect with broader notions of identity, migration and belonging.

To see more work by Teva Cosic, visit - Website / Instagram

︎