IN CONVERSATION WITH:

SHI YAN

SHI YAN

(06.07.22)

In Conversation with Adrian J. Song

Adrian Song: Thank you so much for your time, Shi Yan. You’ve moved around a lot since you were a child, could you tell us about your journey so far and how this has informed your photography?

AS: What was life like for you being locked down in Shanghai?

AS: I love that story about your father’s camera. Do you still have the picture you took of your crush?

AS: (laughs) A secret photo, maybe it’s not even her! Your project, “Plastic Wings”, references the myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Could you tell us more about this link?

AS: I definitely agree when you say, “myth is closer to the truth than the news”. Or perhaps in regards to myth, because of its self-reflexive nature, we could say it’s more ‘transparent’ than the news. I also think it’s really interesting that you say you “gave up generalised expression”, could you talk more about this?

AS: Your images reference impermanence, though in a way, these structures continue to exist through your photographs - perhaps becoming something else altogether. You mention that at one point, “the line between reality and illusion began to dissolve.” If possible, could you describe how you perceive these pictures now?

AS: This discussion reminds me of something Anaïs Nin said, “We see the world not as it is, but as we are.” You refer to the images as clues, and you’re attempting to guide us to “some kind of truth”, as you described. But this can be tricky, because as viewers, we’re also framing your photographs through the context of our own beliefs. How do you find the right balance between opacity and clarity? Or do you perhaps embrace the fact, it is out of your control what people end up taking away from your work?

AS: Photography is one way, how else are you being inspired right now?

AS: “Those Cannot Be Forgotten” sounds like really important work. I have no doubt you’ll find a way to translate these stories in an extremely thoughtful way. Considering the current environment you’re living in, what is it like being an artist living in China?

AS: Thank you so much for your time Shi Yan, I’ve really enjoyed this conversation. What are you up to now, and what do you have planned for the future?

︎

Shi Yan (b. 1998, Buenos Aires, Argentina) lives and works in Shanghai. He graduated from Fudan university and majored in Philosophy.

His ancestry can be traced back to Fuqing, a coastal city in Fujian Province, China. With China's reform and opening-up in the 1990s, his parents travelled to Argentina to do business, before returning in the early 2000s due to the various the economic, political, and social crises. Since his return to China, Shi Yan and his family have lived in many different cities.

His years of constant movement and his studies of the Frankfurt School of philosophy have led to an interest in subjectivity and the experience of the individual in the public sphere.

To see more work by Shi Yan, visit - Website / Instagram

︎

Shi Yan: When I was in elementary school I had a crush on a girl, however my family was moving to a different city soon. So one day I stole my father’s camera without him noticing and took a photograph of her. Since then, photography has been a recording tool for me, which is a kind of retention of perishable time.

During college I encountered many excellent philosophical theories. I also started a business - of which its failure caused me to reflect. Influenced by my girlfriend, as well as another friend of mine, I began to discover the great charm of photography and its potential for conceptual and emotional expression. Since then, I began to study the history of photography systematically.

Now, in retrospect, my journey has made me a sensitive person. I care very deeply about my surroundings and the environment I live in. This sensitivity has caused me to feel alienated at times, but this distance has also given me the space to observe and think.

AS: What was life like for you being locked down in Shanghai?

SY: I stayed at home with my cats and my girlfriend. We were constantly worried about food and supplies. Due to Shanghai's confusing, complex and one-size-fits-all anti-epidemic policies, of course, I was very panicked, anxious, and sad.

AS: I love that story about your father’s camera. Do you still have the picture you took of your crush?

SY: I think I put it in a box. Now I compare the content and style of that photo to Sophie Calle's "Suite Vénitienne”. I probably didn’t even get a photo of her face.

AS: (laughs) A secret photo, maybe it’s not even her! Your project, “Plastic Wings”, references the myth of Daedalus and Icarus. Could you tell us more about this link?

SY: Myth is usually a combination of reality and imagination, and it makes no secret of its fictional elements, to the extent that myth is closer to the truth than news. The polytheism of Ancient Greeks gave Greek mythology a characteristic that it was both secular and sacred. In my view, the uncertainty of myth is the same reason why true art is always so appealing. The Icarus myth is one representative. The establishment of the labyrinth and predicaments, rising and falling, hope and despair, life and death, all of these are involved in the Icarus myth, and also are contained in our time.

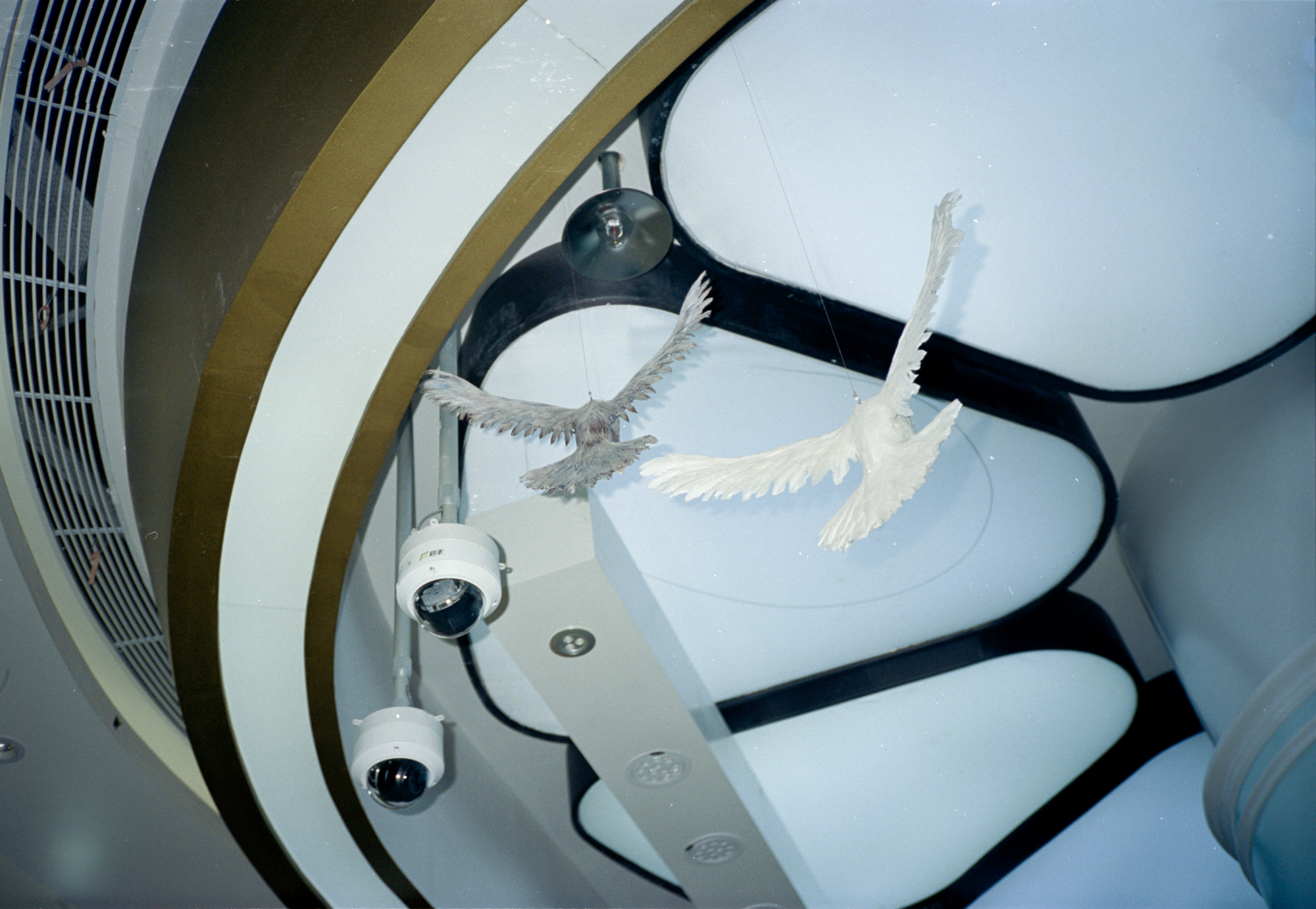

When I walked through the mall during the epidemic, looking at bird models, especially their wings, I immediately associated them with Icarus’s fragile wings. Reflecting on the complex social environment, I am reminded of characters trapped by desire in the myth. In the face of the plague, as Adorno said, "To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric". Beautification and praise are powerless, yet presenting complexity and contradiction is more effective.

What my project attempts to describe is a state of living, which began after the outbreak of the epidemic, and of course it contains the content of the plague more or less. Therefore, the most direct impact of the Icarus myth on my project is that I gave up generalised expression as well as presupposing any definite point of view. Nevertheless, it makes me think about the ways in which history repeats and changes on a sensible level.

AS: I definitely agree when you say, “myth is closer to the truth than the news”. Or perhaps in regards to myth, because of its self-reflexive nature, we could say it’s more ‘transparent’ than the news. I also think it’s really interesting that you say you “gave up generalised expression”, could you talk more about this?

SY: A novel, for example, could have a linear narrative which forms the basis of building its literary world. Images, of course, can have narrative qualities, but this is not its real strength. Especially for photography, its integrated physical properties are deceptive. Although the single image has a ‘studium’, it never indicates the whole truth, in fact, a narrative often limits a photograph’s real potential. For example, if text and a series of images are compared, the former has more specific details, and the latter leaves more space for imagination.

In ‘Plastic Wings’, I gave up generalised expression by implementing various styles. I avoided linear narrative and instead emphasised cohesiveness through symbolism. It is more important, for me, to go into a realm that is more extensive and continues to communicate with personal experience. In my opinion, Mike Mandel and Larry sultan's ‘Evidence’ and Aby Warburg’s ‘Bilderatlas Mnemosyne’ are representative of the abandonment of general expression.

AS: Your images reference impermanence, though in a way, these structures continue to exist through your photographs - perhaps becoming something else altogether. You mention that at one point, “the line between reality and illusion began to dissolve.” If possible, could you describe how you perceive these pictures now?

SY: We all know that a knife is different from a key, but when we want to open a package without a knife, we’re still able to use a key to open it. We would never call a knife a key. However in my example above, the key replaces the function of a knife. In Platonic philosophical terms, the knife and the key share an idea, or a form. This is also the premise of our discussion, and I believe these Platonic philosophical terms reveal some aspects of the “structures” you are talking about.

For example, in ‘Plastic Wings’, colours, symbols and shapes of objects are constantly transforming. But to me, they all point to the same thing. It’s like clues, which are seemingly unrelated, but in the end reveal some kind of truth. When I said “the line between reality and illusion began to dissolve", it’s about history, as well as speculative documentary. In some photos, these scenes do exist in real life. But are they real? You can't figure out the logic in its appearance. Additionally, some scenes that seem ordinary are actually staged. It’s difficult to distinguish reality from illusion because the photos look ordinary and surreal at the same time.

"The line between reality and illusion began to dissolve" is also a feeling I get from interacting with my surroundings. I would describe my photos as stones sinking in a clear but fast-flowing creek, sometimes the stones will be covered by the current from another angle. Occasionally you might throw stones into the creek to see the splash. Sometimes you may want to pick up the stones, but they may be washed away by the current.

AS: This discussion reminds me of something Anaïs Nin said, “We see the world not as it is, but as we are.” You refer to the images as clues, and you’re attempting to guide us to “some kind of truth”, as you described. But this can be tricky, because as viewers, we’re also framing your photographs through the context of our own beliefs. How do you find the right balance between opacity and clarity? Or do you perhaps embrace the fact, it is out of your control what people end up taking away from your work?

SY: Yes, I accept this fact. When I showed my work to French magazines, they perceived depression and environmentalism. While Japanese magazines saw a reflection on technology, My friends said they felt a certain vulnerability and alienation. As you said, " it is out of your control what people end up taking away from your work " , but I believe that truth has different shapes. No matter "environmental issues", "depression", "technology", "fragility", or "alienation", they all seem completely different, but if you think about it, they could have the same destination. This truth is difficult to describe in words, and I can only say: environmental protection and technology come from the use of a kind of power. At a certain level, power is not always indestructible, sometimes it’s even fragile.

The content of the photo is clear, while the "Punctum" of the photo is opaque. I believe that it’s the audience that finds this balance first. In fact, when the viewer is looking for a certain truth, I am also following this truth, and the project itself is more like a short-term balancing point in this process. On the perceptual level, the project can also be described as a certain intersection between fiction and reality. What I can do is grasp their commonalities, like visual commonalities, cultural commonalities, mythological commonalities, and historical commonalities, and finally show this similarity in pictures.

AS: Photography is one way, how else are you being inspired right now?

SY: Photography is my preferred medium, and it naturally has an advantage over others when it comes to dealing with relationships, connections, truth and falsehood, or some ambiguities. Therefore, some photographic works, such as some documentary-style works, often teach me methods of seeing, and reveal the relationships between certain things.

There are many things that inspire me, not only some works of art but also philosophical ideas like the Frankfurt School. But what inspires me the most are "connections", and they usually come from things that are routine in this society, which may be a power relation or behavioural logic. These “connections”also come from news and myth. I need to keep myself sensitive to circumstances around me and try to find out the truth behind it in a way without preset. These are the“connections” that I am talking about, which emerge repeatedly, but are always neglected or overshadowed by something more intense and superficial.

To be more specific, I have been unable to go out due to the lockdown in Shanghai for the past few months. My main sources of inspiration became some pictures from news, some posts on social medias, and some news that could not be reported by Chinese mainstream medias. I have an album on my mobile phone called "Those cannot be forgotten". It contains screenshots of texts or photos that I have saved. Most of them are about personal sufferings that have been covered up by a grand narrative, either blocked from social medias or cannot be reported. The reason why I believe I am inspired by them is not because I can digest these events and take them calmly but because I'm just afraid I might forget them.I hope to turn myself into some kind of converter and transform the logic and truth behind these sufferings into something that can be seen.

AS: “Those Cannot Be Forgotten” sounds like really important work. I have no doubt you’ll find a way to translate these stories in an extremely thoughtful way. Considering the current environment you’re living in, what is it like being an artist living in China?

SY: As an artist living in China now, with so many things happening around me, I feel that artistic expression is urgently needed. Seeing, feeling, and expression is the most important thing.

AS: Thank you so much for your time Shi Yan, I’ve really enjoyed this conversation. What are you up to now, and what do you have planned for the future?

SY: Shanghai just ended the lockdown, and now I'm improving my project plastic wings. After that, I want to do a photo book first, and then I think I want to do a project about Chinese real estate.

︎

Shi Yan (b. 1998, Buenos Aires, Argentina) lives and works in Shanghai. He graduated from Fudan university and majored in Philosophy.

His ancestry can be traced back to Fuqing, a coastal city in Fujian Province, China. With China's reform and opening-up in the 1990s, his parents travelled to Argentina to do business, before returning in the early 2000s due to the various the economic, political, and social crises. Since his return to China, Shi Yan and his family have lived in many different cities.

His years of constant movement and his studies of the Frankfurt School of philosophy have led to an interest in subjectivity and the experience of the individual in the public sphere.

To see more work by Shi Yan, visit - Website / Instagram

︎