IN CONVERSATION WITH:

CLAUDIA IACOMINO

CLAUDIA IACOMINO

(17.03.22)

In Conversation with Adrian J. Song

Adrian Song: This may seem like an odd question, but I'm curious about whether or not you've ever experienced Deja-vu?

AS: The reason I ask is, I’m guessing that’s how it must feel to be reminded of something you’ve forgotten. Is there anything you fear you will forget?

AS: Starting a project which deals with such personal subject matter must have been difficult; how did doing this work impact you creatively?

AS: The project also shares its name with the Greek Goddess, 'Mnemosyne'. Can you tell us more about this link?

AS: That's really interesting. I’ve never made that connection between memory and beauty before. Can you tell us more about the process you go through to create these images?

AS: The work also draws heavily on collage, using archival/scanned imagery in unison with digital photography. What is the relationship between this method of expression and your research so far?

AS: You also mentioned that your interest is to 'understand what memory is made of'. What have you discovered?

AS: Thank you so much Claudia, I've really learned a lot. What are you working on right now, and what do you have planned for the future?

︎

Claudia Iacomino is an Italian artist. She is mainly interested in photographic language and its ability to describe thought rather than reality. Her work focuses on the appearances and the human system of perception, exploring the possible boundaries of visual perception and construction of experience. Even when she explores new media, she does not leave photographic semantics, choosing to exalt the static image as a metaphor for thought.

To see more work by Claudia Iacomino, visit - Website / Instagram

︎

Claudia Iacomino: No, I don’t think I’ve ever experienced Deja-vu. However, I’m not entirely sure. I have many doubts about how we record our memories, that’s why I try to investigate the perceptual systems, the memory and, above all, the tools we use to remember.

I think that sometimes we emphasise ourselves so much in our old memories that we kind of mistake 'mental images' for real memories. It has occurred to me that I have mistaken photographs and videos of my past for actual memories. Which has led to inaccurate memories. Which perhaps leads to Deja-vu.

AS: The reason I ask is, I’m guessing that’s how it must feel to be reminded of something you’ve forgotten. Is there anything you fear you will forget?

CI: I lost my father after a long and devastating illness. In those five years of struggle, when life has worn out so quickly, I started reflecting on the labile memory systems. Memory has to do with images, and memory exists only when someone practices it. These thoughts led me to start working on this project, 'Mnemosyne'.

AS: Starting a project which deals with such personal subject matter must have been difficult; how did doing this work impact you creatively?

CI: I have never used photography for cathartic purposes and 'Mnemosyne' is not really a therapeutic type of work. But working through such intense pain has allowed me to turn the project into a reflection on memory that is not just about what happened to me. 'Mnemosyne' has become an observation of reality. A visual research on the natural subjects of life and death, loss and memory. It concerns everyone.

AS: The project also shares its name with the Greek Goddess, 'Mnemosyne'. Can you tell us more about this link?

CI: The whole creative process has been a research on memory and historical methodologies aimed at its literal unveiling. Mnemosyne, Greek Goddess of Memory and mother of the Muses, is also the title of the artwork by Aby Warburg from which this work takes inspiration from, especially for its historical-visual approach, favouring the idea that Memory is anything but something static that must be transmitted by ceremony, but rather an emotional activator capable of triggering powerful chemical reactions in reality. In other words, ‘able of creating beauty.’

AS: That's really interesting. I’ve never made that connection between memory and beauty before. Can you tell us more about the process you go through to create these images?

CI: My interest is to understand what memory is made of: how to practice it, how it has been powered, where does it go, what it has to do with the images, with the truth, with the memory itself, with the History per se and with the history of the community as a whole. So I started by scanning my father's photographic archive, recovering memories that don’t belong to me: youth, experiences, his views about things in general, interlacing the scanned images with “collateral photographs”: pictures with a therapeutic and cathartic purpose, a study for exploration and reconciliation with oneself.

The aim is to create an Atlas of images able to show how memories work, how they move over time, in a fragmentary and unexpected way, just as the memory is. The recollection is turned into images, open-images in which one can find a story, far from being an individual one but more as a common, collective and recurrent grief.

AS: The work also draws heavily on collage, using archival/scanned imagery in unison with digital photography. What is the relationship between this method of expression and your research so far?

CI: Our memory produces something incomplete and extremely labile. Using tools such as photographs to record reality tricks us into thinking we will possess that memory forever, but instead, it just produces a falsification of memory. Combining archived images and digital images by overlapping them in a collage leads to creating visual connections, connections that are now testimonials of an era, an aesthetic, and not just any frame of a story.

AS: You also mentioned that your interest is to 'understand what memory is made of'. What have you discovered?

CI: Memory is made up of sensorial perceptions that are turned into images. Memory has to do with time but doesn't account for dates, it considers the space as infinite and the time events don't necessarily match with the place they occurred. So I think that this is the main reason why it is challenging to express memories through photographs. Photographs have always been intended as recordings of time events and therefore associated with memory.

AS: Thank you so much Claudia, I've really learned a lot. What are you working on right now, and what do you have planned for the future?

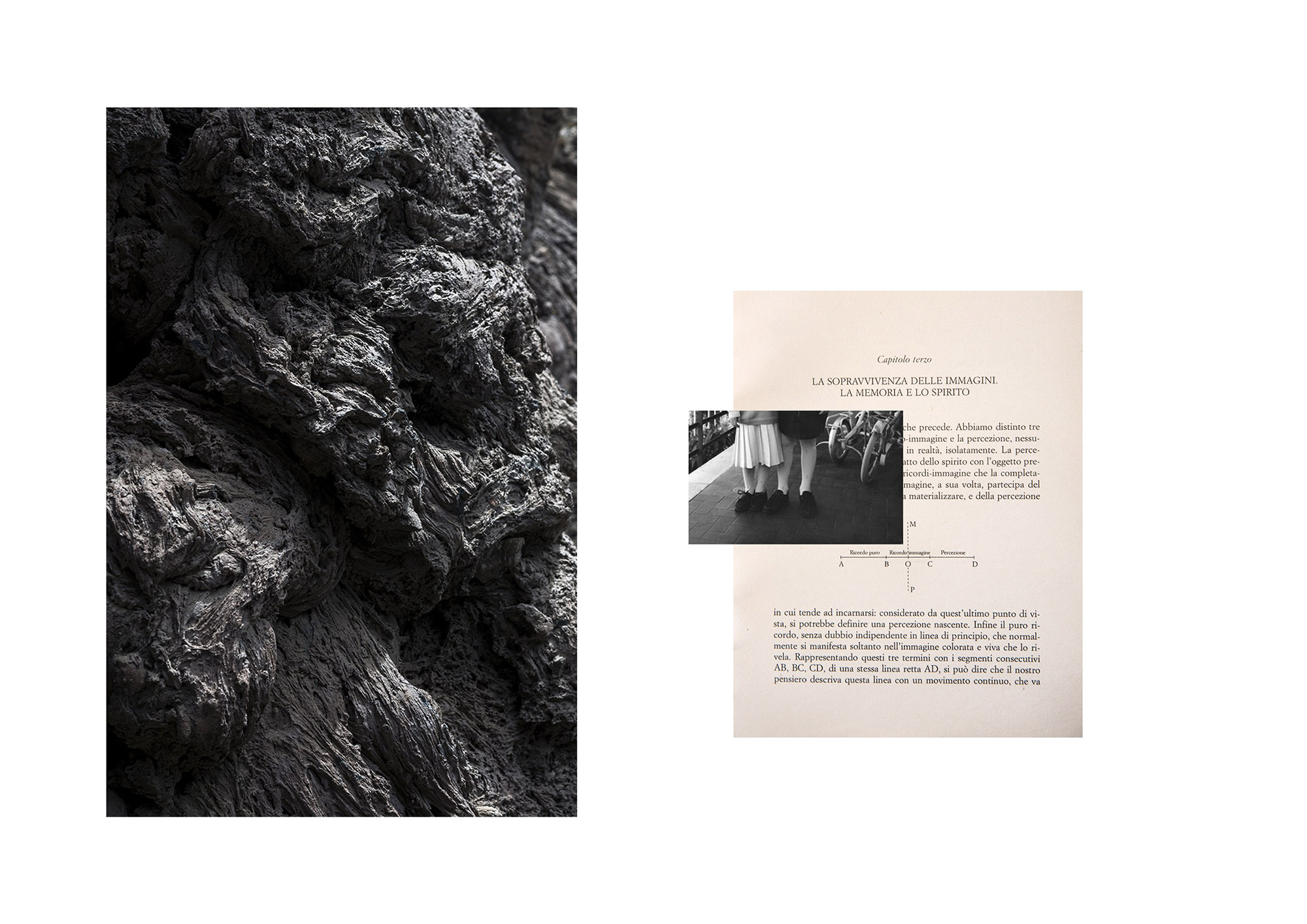

CI: I am currently studying. The topic I'm dealing with is the Vesuvian lava stone. It's not just a stone, but it's a trace of the past. I find it very fascinating as it's something that has exploded, torn down an entire land and settled, then taken its place. The next few months will be challenging and intense.

︎

Claudia Iacomino is an Italian artist. She is mainly interested in photographic language and its ability to describe thought rather than reality. Her work focuses on the appearances and the human system of perception, exploring the possible boundaries of visual perception and construction of experience. Even when she explores new media, she does not leave photographic semantics, choosing to exalt the static image as a metaphor for thought.

To see more work by Claudia Iacomino, visit - Website / Instagram

︎