IN CONVERSATION WITH:

ALICE OLIVER

ALICE OLIVER

(29.07.22)

In Conversation with Sophie Spence

Sophie Spence:

Would you be able to tell us a little about the general themes of your project?

SS: What is the importance of alternative processes in your work?

SS: Why did you choose to expose your images in the moonlight rather than sunlight, how did you develop this process?

SS: Written text comes into play in many of your projects, how do you use text and poetry to develop your creative works and thinking?

︎

Alice Oliver (b. 1998), is a research-driven visual artist and writer whose practice focuses on our relationships to our surrounding natural landscape, and within a contemporary feminist discourse, provides a retelling of the deeply intimate connections between human and non-human nature. In an ongoing lyrical exploration into the relationship between the ancient landscape surrounding her and photography's materiality, cyclical traces emerge as Alice unveils the natural cycles and suppressed narratives by visualising the rituals of the female body.

Alice is also the founder and curator of SOLA Journal, an artist-led platform facilitating exploration and conversations within contemporary visual art, both online and in print.

To see more work by Alice Oliver, visit - Website / Instagram

︎

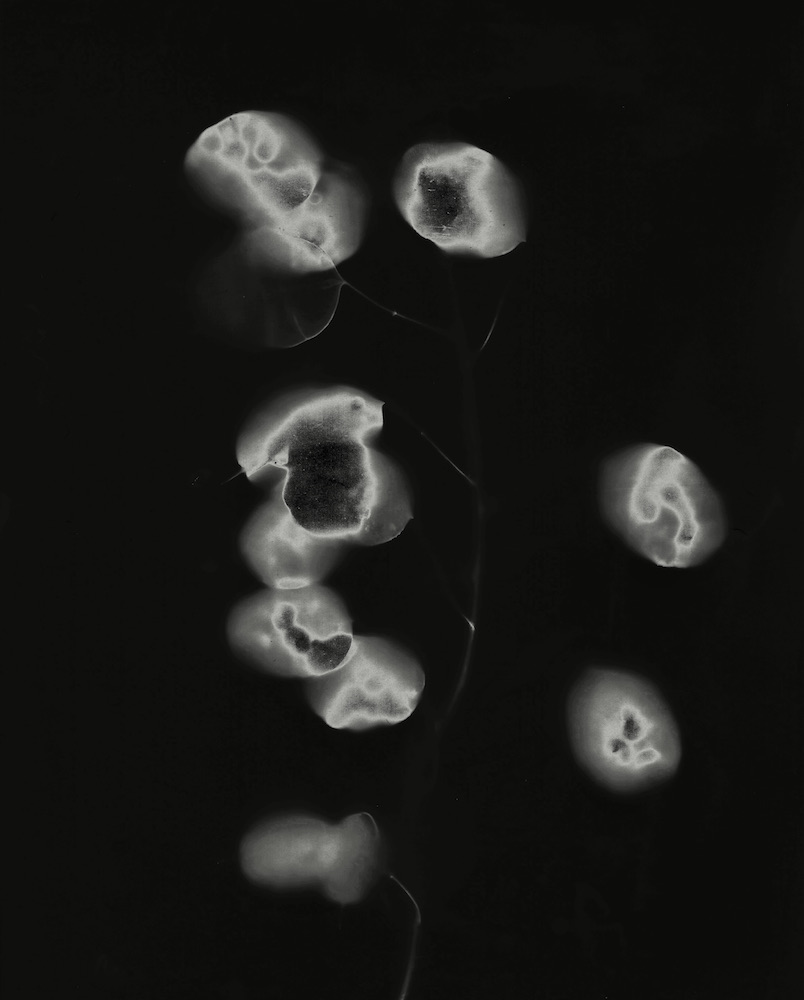

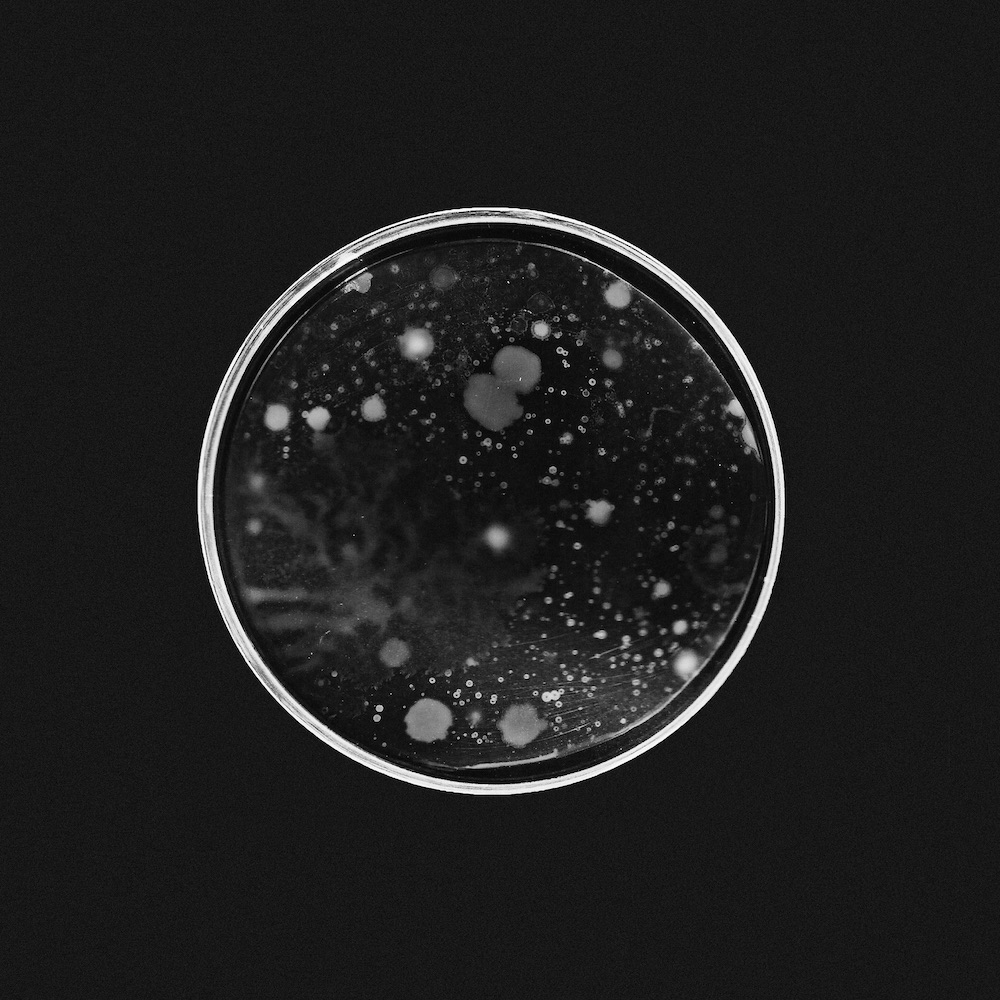

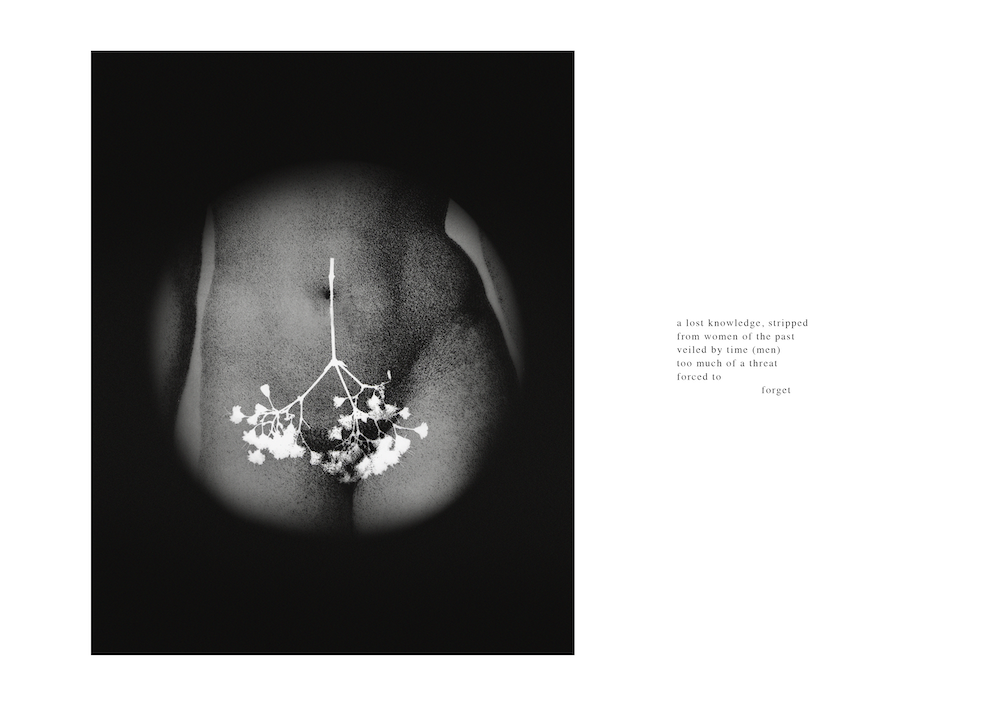

Alice Oliver: This body of work was born out of an investigation into the cyclical links between women, the moon and the land. Primitive research into these connections revealed the importance of plants within the history of women’s bodily autonomy. Abortion and contraception are by no means modern interventions, and for millennia, women have utilised plants to control and regulate fertility. Our hedgerows and waysides are still rich with the plants once used as emmenagogues and abortifacients.

By unveiling lost narratives, and visualising the rituals of the sexual and reproductive female body, the ancient knowledge that was stripped from women in the face of modern medicine and religion, is revealed. This investigation seeks to awaken us from our latent and patriarchal past and, sadly, our present. In a world where men still make decisions regarding women’s bodies, these skills of caring for, healing, and maintaining women’s bodies are still considered a threat.

Through the preservation or reclamation of ritual, both within the history of women’s bodily autonomy and within photography itself, I feel it is important to bring these histories to light in a contemporary context, to remind us of the critical relationship between the cycles of our bodies and cycles of the earth.

SS: What is the importance of alternative processes in your work?

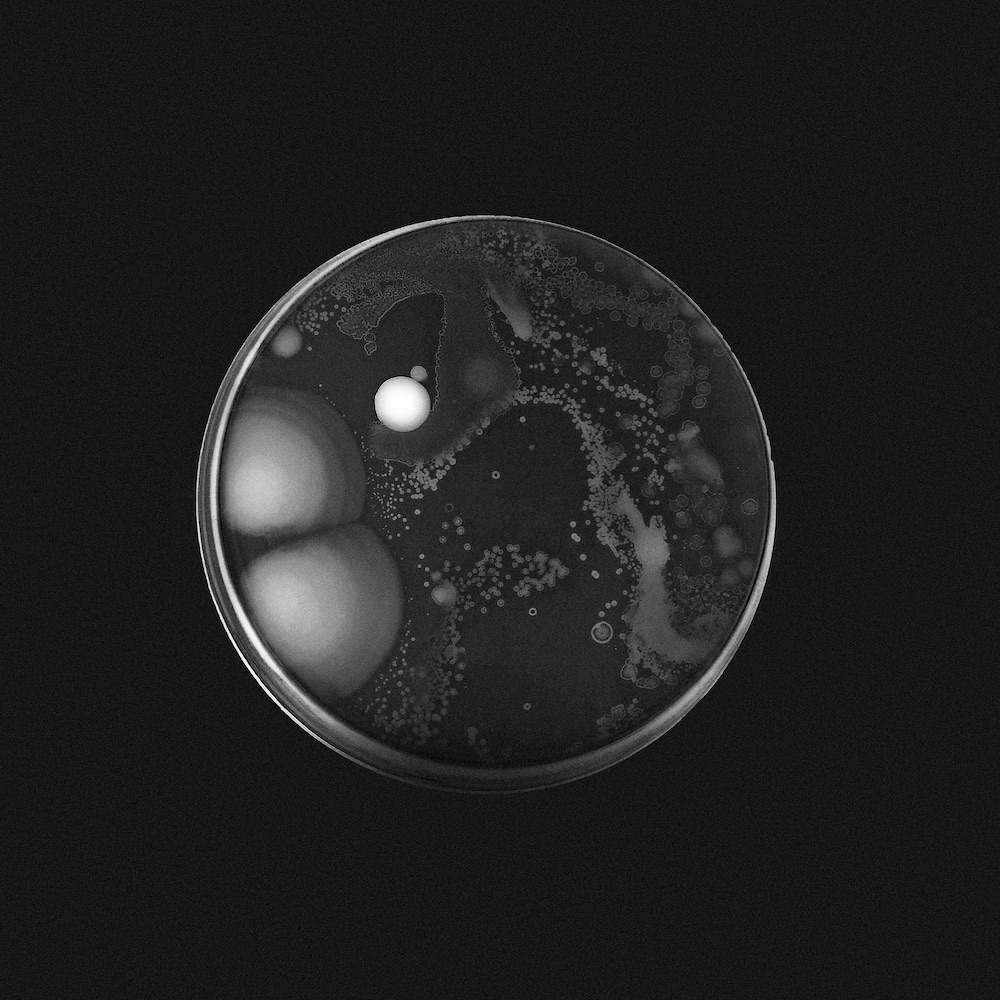

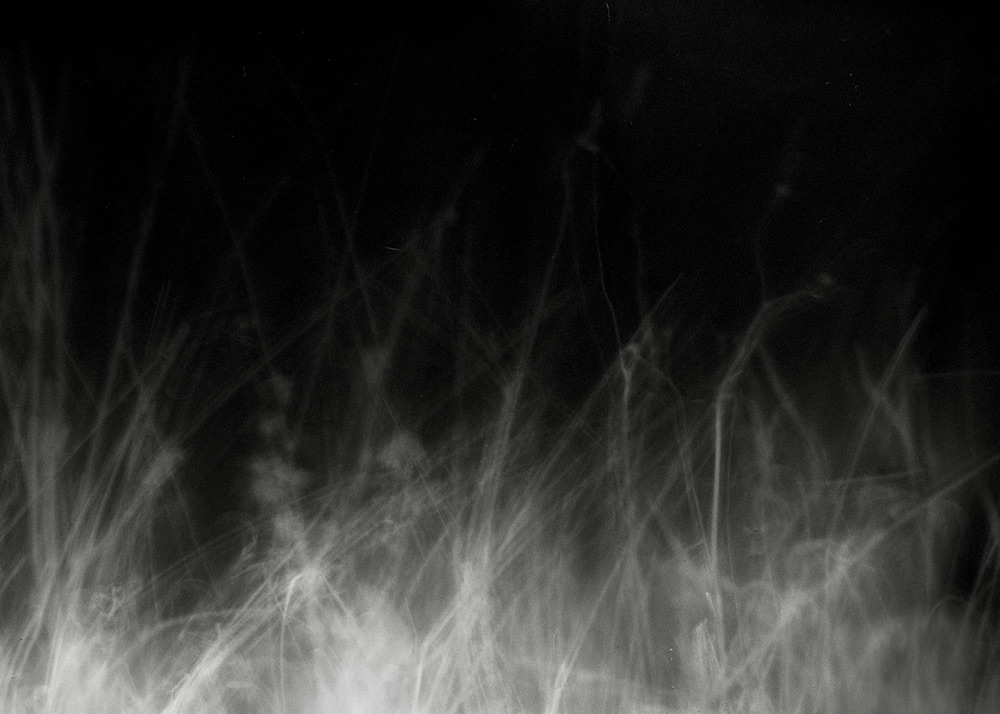

AO: There is a combination of reasons why I chose to step away from the digital processes and utilise alternative and camera-less processes. The main reasons revolve around the idea of ritual. The ritualistic process that women used to go through, sourcing and picking the plants, brewing a tea or making a suppository, is such an important part of this forgotten history that I wanted to mirror within the process of the work I was making. It was a tactile, sensitive and slow process that depended on the Earth and the cycles of life. Each month I tracked the cycles of the moon and the weather waiting for the full moon on a clear night, I feel that the process of my Lunargrams mirrored the ethereality of the ritual these women went through perfectly.

This idea of the ritual is also apparent within photography itself, something that was also somewhat lost in the face of the digital. Walter Benjamin's idea of the Aura, which he defined as a characteristic inherent in a piece of art that cannot be conveyed by mechanical reproduction techniques, such as digital photography. This idea of ritual that Benjamin writes about in regards to the aura of analogue photography is so important to my practice, in regards to the loss of the ritualistic knowledge of healing, caring for and maintaining the sexual and reproductive female body, but also in regards to the photographic image. To me, this idea of the loss or decay of an aura through digital reproduction feels really important to the physical process of the work I make. There is a ritualistic nature to the Lunargram process I go through. As I stand on the edge of a field, by the wayside, surrounded by a vast pharmacopoeia of plants used for contraceptives and abortifacients, all captured in a transient moment, under the light of a full moon. The aura of this process, the history it holds and the importance it has in the contemporary world, is somewhat dismantled and lost as soon as these images are digitised to be seen on a screen.

SS: Why did you choose to expose your images in the moonlight rather than sunlight, how did you develop this process?

AO: This whole body of work was born out of an obsession or connection I have had with the moon since I was very young. I decided very early on that it was important to utilise the light of the moon, which has such deep intimate and cyclical connections with women, to quite literally shed light on the suppressed and forgotten histories of women's control over their reproductive bodies. The moon has also always been connected with women and fertility and similarities have been found between the menstrual cycle and the lunar cycle. To me the use of moonlight holds so much more political, historical and contemporary power than that of artificial light or even sunlight. After all, it is the same moon that has looked over these women centuries ago, I guess by using the moonlight, it connects me to these women throughout history. To go through a cycle of new growth is consistent with these ancient cyclical ideas of ovulation, flowering, harvest, degeneration, and replenishment. Tying us not only to one another but also to non-human beings we find within nature. Revealing how intrinsically interconnected humans are within the natural processes of the land and the stratosphere beyond.

SS: Written text comes into play in many of your projects, how do you use text and poetry to develop your creative works and thinking?

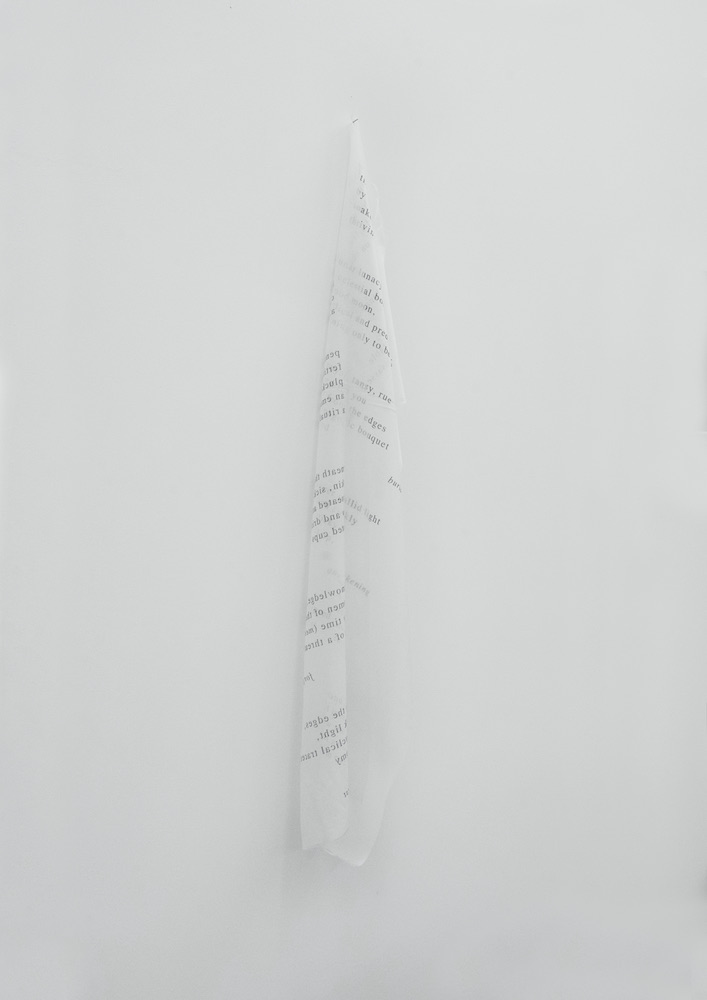

AO: With my work, I found that the context was almost just as important as the images I was making. I wanted to step away from your average project statement plaque on the wall and create something more intimate and part of the work rather than just a description. I thought that poetry would lend itself to the themes in this body of work and the ethereal methods in which the work was made, whilst also allowing me to give the work some context without over-explaining it to the audience. For my most recent exhibition, I chose to print the poem onto a piece of cotton, linking to the cotton these wise women used to make plant-infused suppositories. I hung it on the wall like a towel or bed sheet, meaning the audience had to interact, lift a corner and pull it out in order to read the whole poem. I think this mirrors the secretive ways they would have passed on the information, women to women, about each plant, its dosage and its purpose. By physically revealing the poem, you are also revealing the loss and suppressed knowledge of women. Some art needs no description, what you see speaks for itself, but often art, especially research-based art, needs context and I personally think poetry is a great tool when it comes to contextualising photographic work.

︎

Alice Oliver (b. 1998), is a research-driven visual artist and writer whose practice focuses on our relationships to our surrounding natural landscape, and within a contemporary feminist discourse, provides a retelling of the deeply intimate connections between human and non-human nature. In an ongoing lyrical exploration into the relationship between the ancient landscape surrounding her and photography's materiality, cyclical traces emerge as Alice unveils the natural cycles and suppressed narratives by visualising the rituals of the female body.

Alice is also the founder and curator of SOLA Journal, an artist-led platform facilitating exploration and conversations within contemporary visual art, both online and in print.

To see more work by Alice Oliver, visit - Website / Instagram

︎